The Weak Dollar Gambit: Mar-a-Lago Edition

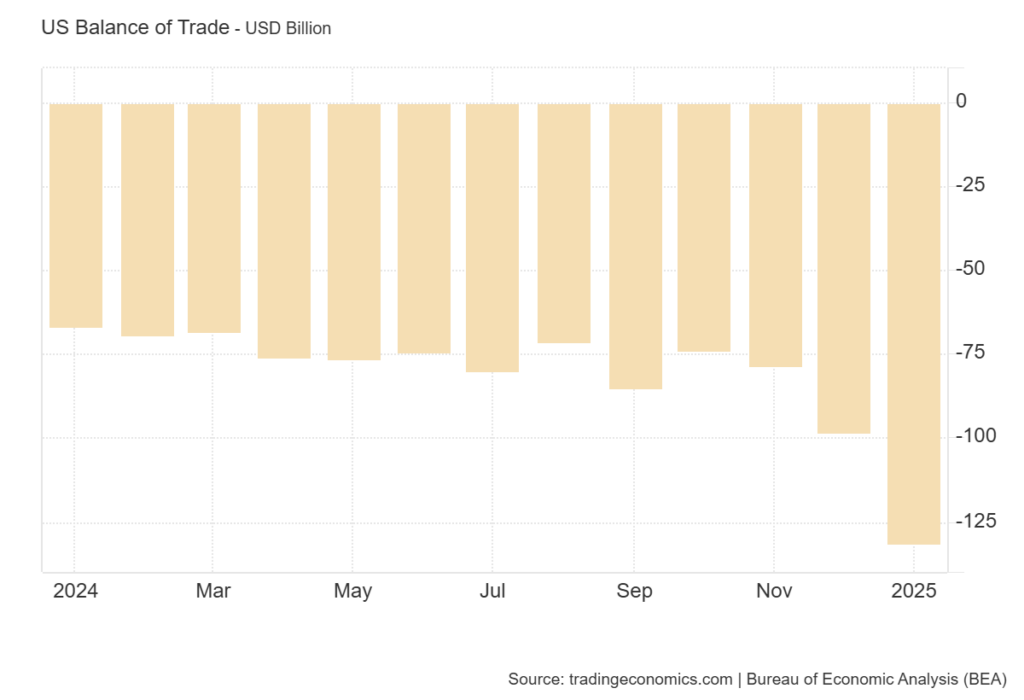

As US President Donald Trump’s administration floats the idea of a “Mar-a-Lago Accord” to engineer dollar devaluation and reshape global trade, we face a potential watershed moment in international finance. Drawing parallels to the 1980s Plaza Accord, this ambitious currency intervention strategy promises quick fixes but risks profound consequences while overlooking America’s deeper structural challenges.

The story of deliberate currency manipulation on the global stage has a critical historical reference point.

On September 22, 1985, finance ministers from the United States, Japan, West Germany, France and the United Kingdom gathered at New York’s Plaza Hotel to sign what became known as the Plaza Accord. Their mission was straightforward yet bold: to orchestrate a deliberate depreciation of the US dollar, which had appreciated approximately 50% against major currencies between 1980 and 1985.

The context for this intervention was clear. The Reagan administration’s tight monetary policy under Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker combined with expansionary fiscal policies had driven up long-term interest rates, attracting capital inflows that strengthened the dollar. This appreciation had devastated American manufacturing competitiveness, widened the current account deficit to 3.5% of GDP and prompted Congressional threats of protectionist legislation.

The immediate results seemed encouraging – the dollar fell 4% against major currencies just after the announcement. Over time, the US trade deficit with Western European nations declined, though crucially, it failed to meaningfully impact the deficit with Japan. More ominously, some analysts connect the Plaza Accord to the Japanese asset price bubble and subsequent “Lost Decade” of economic stagnation, though the causal relationship remains debated.

Fast forward four decades and we face a similar conversation with potentially greater consequences. The so-called “Mar-a-Lago Accord,” named after President Trump’s Florida estate, represents not an actual agreement yet but a developing framework for reshaping America’s position in the global economy.

At its core, the proposal shares the Plaza Accord’s fundamental goal: engineering a weaker dollar to boost American exports and reduce trade deficits. However, it would employ more dramatic mechanisms. According to reports, it would involve forcing foreign creditors to exchange their Treasury holdings for 100-year, non-tradeable zero-coupon bonds that would only pay at maturity. This debt restructuring would allegedly reduce interest payments on US federal debt, which had exceeded $1 trillion annually for the first time in 1981.

Additional components reportedly include implementing higher tariffs, creating a US sovereign wealth fund and shifting more security spending to allies. The intellectual architecture comes primarily from Stephen Miran, Trump’s nominee to lead the White House Council of Economic Advisers, who outlined these ideas in a November 2024 paper. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has similarly predicted “some kind of grand economic reordering”.

Misdiagnosing Economic Challenges

The Plaza Accord and the proposed Mar-a-Lago framework share a fundamental flaw – both treat currency values as primary causes rather than symptoms of deeper economic imbalances. Currency manipulation offers the political allure of quick results without demanding difficult structural reforms.

The Plaza Accord’s limited success underscores this point. While it reduced deficits with Europe, it failed with Japan because Japan’s trade surplus stemmed from structural conditions resistant to monetary policy adjustments. The country’s import restrictions created barriers that even a stronger yen couldn’t overcome.

Similarly, America’s current economic challenges extend far beyond dollar valuation. Their productivity growth has slowed, infrastructure investment has lagged, and educational outcomes have stagnated in key areas. Workforce development, innovation ecosystems and regulatory coherence require attention that no currency intervention can substitute.

The debt swap component reveals another troubling aspect – the prioritisation of short-term relief over long-term sustainability. Pushing debt obligations into a 100-year timeframe merely kicks financial responsibility down the road to future generations. This generational burden-shifting contradicts principles of sound fiscal management.

Financial markets are taking notice. While bond traders seem relatively calm and equities hover near record highs, market strategists like Jim Bianco warn that Trump’s administration may be “more bold than people now even expect” and could “completely shake up the global financial system”.

This understatement reflects the profound implications of deliberately weakening the world’s reserve currency. The dollar’s global role confers what former US Treasury Secretary John Connally once called “our currency, but your problem.” A rapid devaluation would trigger significant wealth redistribution globally, potentially destabilising emerging markets with dollar-denominated debts while disrupting international trade flows that depend on the dollar’s stability.

Moreover, the approach risks triggering retaliatory measures. The Plaza Accord succeeded largely because it represented multilateral consensus. An adversarial American imposition would likely provoke countermeasures, potentially igniting currency wars that leave everyone worse off. China, whose cooperation would be essential for any meaningful global realignment, would have little incentive to accept disadvantageous terms.

Learning From History or Repeating It?

Rather than reviving yesterday’s solutions for today’s problems, American policymakers should focus on enhancing fundamental economic competitiveness. This requires uncomfortable acknowledgment that our challenges require patient, structural reforms rather than dramatic interventions.

First, fiscal discipline must replace reliance on cheap debt. The federal interest burden threatens to crowd out productive investment and constrain future policy options. Second, targeted investments in education, infrastructure and research can rebuild America’s productive capacity more sustainably than temporary currency advantages. Third, regulatory modernisation could reduce compliance burdens while maintaining necessary protections.

International cooperation, not confrontation, offers the most sustainable path. The Plaza Accord worked to the extent it did because it represented coordinated action, not unilateral demands. Today’s more complex global economy requires even greater collaboration. A modern approach to international economic governance should include emerging economies and address technological transformation, climate transition and digital finance.

—

The Mar-a-Lago proposal represents a seductive shortcut – the promise of improved trade balances and industrial revival without difficult domestic reforms. Yet history suggests such interventions rarely deliver their promised benefits and often produce unintended consequences.

The Japanese experience following the Plaza Accord stands as a cautionary tale. While debate continues about causality, the combination of rapid currency appreciation and compensatory monetary stimulus contributed to asset bubbles whose eventual collapse damaged the economy for decades.

The global economy has transformed dramatically since 1985. Supply chains span continents, digital commerce transcends borders, and financial flows move at electronic speed. Using yesterday’s tools to address today’s challenges is unlikely to work.