The Invisible Subsea Artery

Simply calling undersea cables the ‘invisible arteries’ of the digital economy isn’t enough. Governments must take proactive measures, particularly in the arduous task of practically implementing resilience through the entire process, from anticipating and absorbing shocks, to ensuring rapid restoration capabilities and building adaptive systems which learn and evolve. These are tasks which require sustained commitment and investment, and perhaps most importantly, decreased red-tapism and far-improved coordination both within the government bodies and between government and industry. Policy frameworks like the EU Recommendation or the New York Statement are mere starting points, the devil lies in the implementation.

It goes without saying – market emotion and hot air alone are not enough to sustain the global economy. The literal backbone of our globalized society is made up of thousands of kilometers of fiber-optic cables that run beneath the waters. In fact, by some estimates, more than 95% of intercontinental data traffic is carried via such cables. These invisible glass threads probably carry every email, trade and financial transaction that takes place across the ocean floor, mostly irrelevant to politicians. They were a ‘hidden infrastructure’ that was mostly left to the private sector to build and run, concealed away from official concerns. Not anymore.

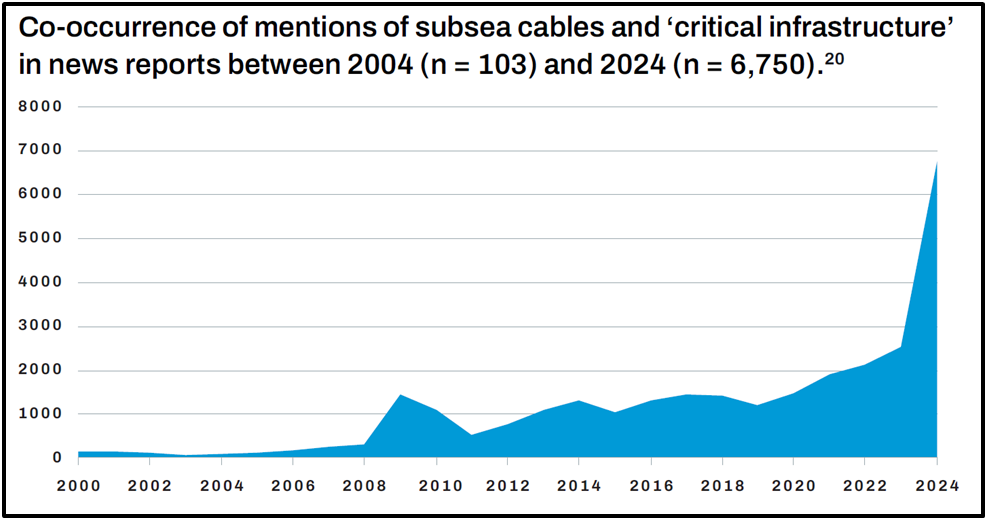

Source: UNIDIR

For reasons that should make every market-watcher pay heed, subsea telecommunications cables have suddenly become quite the hot topic. But why the sudden attention? The increasing ‘fracturing of the international system’ and increased ‘technological competition between the major powers’, according to a recent report from the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR), have woken governments up, as has a series of recent high-profile occurrences, some unintentional, others suspiciously not. Governments are finally coming to the realization that these are essential ‘critical infrastructure’ (CI) that has a ‘debilitating effect on national security, public health and safety, economic stability, or a combination of these’ if disrupted, with the potential to cause widespread regional or national outages that could result in ‘immense’ financial losses.

As the report emphasizes, developing resilience is essential to subsea cables becoming crucial to policy and practice. Consider resilience as a cycle rather than a static state; it is the capacity of a system to foresee, withstand, absorb, react to, recover from, and — most importantly — adapt to shocks. Three core capacities — ‘adaptive’, ‘restorative’ and ‘absorbent’ — are emphasized. This methodology, which draws on the larger body of CI literature, provides a helpful prism through which to assess whether government initiatives are merely adding regulatory theater or genuinely enhancing resilience.

Preparedness is Only the First Step – The ‘Before’

Currently, most State practices fall under the ‘absorptive capacities’ rubric, where ‘security and resilience scaffolding’ — preventive measures, redundancy, and preparedness plans — are put in place. In addition to performing risk assessments and incorporating subsea cable security into national preparedness plans, researchers have observed governments updating, simplifying or re-aligning their regulatory frameworks. Even the release of financial resources for personnel and equipment, especially for marine domain awareness and defense strategy informing, might be aided by a criticality designation.

This emphasis makes intuitive sense. The goal of governments – to promote network variety and reduce redundancies – means strengthening physical protection, enhancing spatial isolation from other marine activities like fishing and anchoring (which, incidentally, continue to be the main causes of damage during peacetime), and simplifying installation permissions.

For example, the EU is pressuring member states to map infrastructure, stress-test operators, apply security standards and carry out regular risk assessments, while aspects like supply chain security and cybersecurity, typically not addressed by older frameworks, are being included in the US-led Joint Statement on the Security and Resilience of Subsea Cables.

The biggest problem with this, however, is that the implementation and maturity of such initiatives vary significantly from country to country, exacerbated by limited conceptual clarity and often-conflicting viewpoints — is this a telecom problem? A cyber problem? A problem with marine security? The answer, more often than not, is ‘all of these and much more,’ necessitating coordination within a horde of government bodies, which is proving to be extremely challenging to do. Coordination with industry, between jurisdictions and within governments is still very difficult.

Additionally, there is a significant chance of government regulatory underreach or overreach, leading to significant ‘additional expenses and burdens’ resulting from such policies for both industry and the government. Resilience problems too arise for both connected states and businesses due to complicated or uneven regulatory settings in the various nations where cables are installed.

While protecting these vital arteries is the intention, it would be prudent to ask if bureaucracy is standing in the way of improving resilience and even unintentionally weakening it, making it more difficult, slow, or costly to install and fix cables (such as licensing delays in the US and China versus more efficient procedures in Denmark/France).

The Restorative Lag – The ‘During’

The ability to ‘re-establish performance as rapidly as possible’ — including emergency operations, contingency plans and getting ‘the right people and resources to the right places’ — is unequivocally essential to the process. Crucially, the cable itself needs to be repaired quickly and precisely.

The reasoning is clear: time is literally money. A major cable outage results in lost production, halted trade and disturbed financial flows every hour. A strong maintenance and repair ecosystem is crucial to this healing ability. However, nations’ knowledge of this specialized sector of the industry was obscure until recently.

This vulnerability has finally been acknowledged. In-depth research is being conducted in nations like the UK and India to determine their maintenance requirements and possible funding shortfalls. The EU too is promoting collaboration on repair capabilities, and measures to guarantee resilience in this domain are part of its action plan. From ‘lengthy permitting processes’ for repair vessels to backlogs and the availability of specialist ships, spare cables, and the highly qualified labor needed, we must comprehend the fundamental problems that cause delays in repair.

Changes in the industry environment, such as some enterprises switching from maintenance to installation or hyperscalers allegedly decreasing costs, can affect the availability of vessels at the most critical times. These are real, potentially expensive chokepoints in the system’s self-healing capabilities, not merely theoretical security risks. It is not only a security consideration to invest in comprehending and maintaining this ecosystem; doing so is also economically necessary to reduce downtime and preserve value.

The Adaptive Challenge – The ‘After’

Learning from accidents, making adjustments, updating plans, changing processes and investing in teamwork and expertise are all part of this. It entails keeping regulations ‘nimble and dynamic’ and adjusting to emerging issues such as shifting ownership arrangements, climate change and maritime spatial planning.

However, as research illustrates with instances like the Red Sea or 1993 Shetland oil tanker disasters, inaccurate public reporting frequently fueled by geopolitical conjecture can divert attention from the actual, enduring causes of cable damage and obstruct the implementation of effective policy solutions. A common situational awareness paradigm and improved, more objective event reporting is the need of the hour. To comprehend dangers in advance and effectively communicate information, including sensitive information, the United States, for example, is realizing the necessity for “improved internal coordination” and better procedures for interacting with industry. With its ‘one stop shop’ lead entity, Singapore too presents a possible template for managing the intricate policy environment.

This is yet another area where the “whole-of-government” coordination problem exists as well. How can defense strategists concerned about undersea warfare effectively communicate with telecom license regulators? What is the relationship between the need for different routes for national security and environmental concerns regarding cable laying? It is crucial to balance these conflicting “equities,” which are arguably frequently mismanaged.

A long-term vision and approach to subsea cable policy and regulation is ultimately necessary for successful adaptation. Without it, initiatives run the risk of being reactive, dispersed, and possibly harmful to the very goals nations are trying to achieve with digital transformation. This adaptive puzzle includes working with academic institutions, utilizing new technologies (such as sensor-equipped cables or quantum communication), and having open conversations about difficult realities (such as state-sponsored cyber operations).

—

The objective must be to build robust and open systems for exchanging information so that responses are based on facts rather than merely geopolitical concerns. Subsea cables’ categorization as essential infrastructure won’t result in true economic security and societal resilience until then. Anything less is merely regulatory noise on a crucial frequency.

Read UNIDIR’s report ‘Achieving Depth: Subsea Telecommunications Cables as Critical Infrastructure’ here.