The Gold Rush

Once regarded a supplementary asset by investors, gold has today become a cornerstone of financial security for central banks, wealthy families, and institutional investors – evolving from a passive hedge to a symbol of resilience and enduring stability.

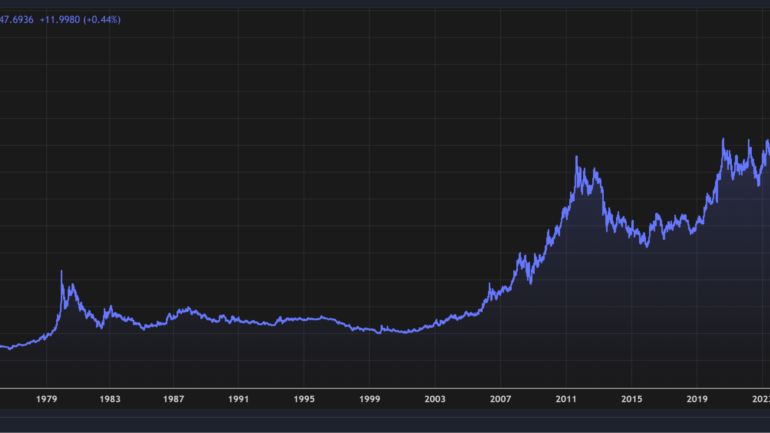

A resurgence in gold prices has painted the global economic landscape with a renewed hue, marking a 38% surge to over $2,700 per troy ounce – a level of demand unseen in years. This surge is more than a response to fluctuating interest rates or fleeting investor optimism. Rather, it underscores a deeper psychological shift in global finance, where geopolitical tensions and inflation concerns have recalibrated the perceived stability of traditional financial assets. Investors, ranging from individual buyers to central banks, have reoriented their focus toward gold, signaling that financial systems once deemed invincible are now seen through a lens of caution.

The Age of Gold, led by Central Banks

Central banks, whose investments typically favour stability over rapid returns, have been leading the charge in amassing gold. Countries such as China, Turkey, and India have each purchased hundreds of tons of gold, with the World Gold Council noting that many banks now prefer to store gold domestically to protect against the risk of foreign asset seizures.

The case of Russia’s frozen currency reserves after its invasion of Ukraine underscored the vulnerability of even the largest central banks to geopolitical decisions by Western powers. Gold, which can be easily liquidated in politically neutral markets, has therefore grown in appeal as a “weaponisation-proof” asset, offering central banks a hedge against the dollar-centric global economy’s volatility.

Interestingly, while institutional investors typically downplay gold, family offices – the investment firms of the ultra-wealthy – are also hedging their bets with gold. Their demand has pushed up gold-backed lending, especially in Asian markets like India, where the economy’s growth has driven a cultural resurgence in gold purchases. These investments echo a widespread scepticism about traditional assets, emphasising gold’s role as a stable, low-correlation asset that insulates portfolios from broader market swings.

The Disconnect with Interest Rates

One unusual feature of this surge is its seeming detachment from real interest rates. Gold prices typically decline when yields on government bonds are high, making bond investments more appealing. But despite rising yields on inflation-protected U.S. Treasuries, gold’s appeal remains strong. This disconnect hints at a broader issue: investors may now see gold as an enduring asset, one that transcends the monetary policy cycles that dictate bond yields. Whereas bonds fluctuate with inflation and interest rates, gold’s appeal appears rooted in an unshakable foundation – its resilience against both political and economic crises.

The recent wave of central bank purchases exemplifies this shift. Normally, high yields would drive gold out of central bank reserves in favour of bonds, but gold’s unique appeal as a crisis asset has overshadowed yield considerations. In this sense, the behaviour of central banks is reshaping gold’s function from a backup to a frontline asset. The Economist aptly describes this shift as part of a new “golden age,” where old assumptions about asset value and security are being reevaluated in light of modern threats.

The Rise of the “Golden Neutrality”

Gold’s newfound popularity is fuelled by what can be called “golden neutrality” – the perception that gold transcends political alliances and economic sanctions. This neutrality is appealing to countries at risk of sanctions, such as Russia and Iran, and even to nations without contentious foreign policies, like Singapore and Poland. For these countries, the goal is not just economic stability but an assurance of self-sufficiency. Central bankers are particularly drawn to gold as a form of insurance against what the Invesco survey calls the “weaponisation” of reserves, which can occur when Western governments sanction countries by freezing foreign-held assets.

Poland’s recent accumulation of gold exemplifies this approach. Adam Glapinski, president of Poland’s National Bank, articulated a perspective increasingly common among central bankers: gold’s worth lies not just in financial stability but in its status as a crisis-proof asset. By converting part of Poland’s reserves to gold, Glapinski has essentially “crisis-proofed” a share of his country’s wealth, a measure that many other countries are likely to adopt in light of recent events.

With central banks and private wealth leading the way, institutional investors are eyeing gold as well. Analysts like Goldman Sachs forecast that institutional investments in gold exchange-traded funds (ETFs) will rise as interest rates stabilise or decline. Even a modest central bank rate cut of 0.25% could lead to a 60-ton increase in ETF gold holdings, valued at approximately $5 billion.

This shift may also be a reaction to the realities of inflation. Unlike stocks or traditional assets, gold is prized for its resistance to inflationary erosion, which recently spiked in several Western economies. This resistance, coupled with growing demand from private and institutional investors, may position gold as a critical asset in future investment portfolios. However, the very fear that drives these investments – of market instability and geopolitical conflict – also underscores gold’s limitations. After all, it yields no income, a fact that may limit its appeal among institutional investors who typically favour income-generating assets.

Gold’s Resilient Role Amid Crisis

As global investors diversify portfolios to manage rising risks, gold’s role as a “liquid asset” may be an understatement. For many governments, gold functions as a covert means of financial flexibility. Amid the sanctions following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, for instance, Swiss imports of gold from the UAE spiked – likely due to Russia’s covert sale of gold through the Middle East. This circumvents Western sanctions, a move emblematic of gold’s resilience in times of financial isolation. Small and easily transportable, gold has a strategic mobility that is hard to replicate in other assets. Gold’s ability to be smuggled, melted, and sold worldwide grants it unparalleled liquidity under crisis conditions. While sanctions can freeze bank assets and seize real estate, gold remains elusive, offering an exit route for countries in dire situations. This adaptability makes gold an essential part of any crisis management toolkit, whether for governments evading sanctions or investors seeking financial stability in an uncertain world.