GDP vs Thriving, And A 200,000-Strong Survey

Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the long-held gold standard for a nation’s success, fails spectacularly in capturing the very nuance – happiness, meaning, connection, purpose and general well-being – that makes life worth living. Findings from the recent Global Flourishing Study is shaking up how we think about national progress.

For decades, economic indicators like GDP have been the main markers for assessing a country’s progress. While it is pretty straightforward and measurable, it falls far short in determining the actual state of a nation, like attempting to assess a complicated ecosystem’s health based solely on the tallest tree’s height. You lose out on the biodiversity, soil quality, the interconnectedness of it all.

The volume of economic output should not be the ultimate objective, the one that matters most to societies and the people who live in them. It is, as recent research from the reputed Nature journal pointed out, a state in which everyone is happy. Happiness, health, a feeling of purpose, solid relationships and financial stability are all important, but so are thriving communities and a healthy environment. It’s not just the economic rhythm; it’s the entire symphony. And on that front, our measurement efforts have been highly inadequate.

What is causing us to lag so far behind on something so fundamental? Primarily, because quantifying human flourishing is a really difficult task that is much more involved than counting transactions or figuring out manufacturing production. This isn’t just a matter of choosing to do better; it’s intrinsically difficult, experts have often made abundantly clear.

The Many Faces of Flourishing

Flourishing isn’t a single dial you can turn. It’s multidimensional. If you think about all the things that make a life good, the list becomes incredibly long, incredibly fast. Happiness, meaning, the quality of your relationships, your income level, your health – these are distinct facets. And the kicker: they don’t always move in lockstep. You might find, as the sources point out, that people in wealthier nations report higher life satisfaction and financial security, which perhaps isn’t surprising. But remarkably, they often report lower levels of meaning or deep relationship satisfaction compared to those in middle-income countries. Sweden, a poster child for life evaluation, ranks far lower on meaning. Is that the trade-off to be made to be regarded as a wealthy nation?

That is perhaps why a single survey question like the one in the World Happiness Report – the ‘Life Evaluation Index’ asking respondents to rank themselves on a ‘ladder’ of life – is not enough. Experts say this question lacks a certain degree of nuance, swaying people to primarily consider wealth and status in their answers, skewing perception away from relationships or ‘purpose’. While meaning and social connectivity fared better during the COVID-19 epidemic in the United States, for example, opinions on happiness, health and finances fell. This crucial distinction is overlooked by a straightforward ‘life satisfaction’ score.The distinction between the objective and the subjective obviously pops up in such a scenario.

While there is much objective data – income levels, literacy rates, life expectancy – how exactly are highly qualitative and subjective aspects of life to be quantified? Do people feel connected, safe, hopeful? The attempt to assess this sense of well-being, just as crucial and far less routinely measured, is the piece of the puzzle that has left researchers scratching their heads for aeons. Two people in similar objective circumstances – same job, same pay, same social setting – might have vastly different subjective experiences: one feels connected, the other lonely. Does increased wealth automatically lead to increased fulfillment? The evidence is multifaceted and policy decisions often have to make implicit trade-offs without clearly understanding causal pathways and transmission mechanisms.

Mind the Gap

Quantifying what ‘flourishing’ means is difficult between even two people, let alone countries or a standardised global scale. Terms like ‘happiness’, ‘purpose’ or ‘satisfaction’ are difficult to translate accurately and vary vastly between languages and cultures. A treasured value in one society – such as individual autonomy and agency – might hold little significance in places that value balance, harmony or collective well-being. Failure to capture this difference is among the biggest risks of a single questionnaire.

Then there is the methodology problem. Measuring well-being at any one time is challenging enough, but figuring out what makes individuals thrive over time is even more challenging. Longitudinal studies that follow the same people are necessary to provide meaningful knowledge. However, association is not causation, and separating the two requires extensive, trustworthy data sets as well as careful research to account for external factors. Another element of complication is introduced by human biases in self-report surveys, such as the unconscious self-deception or the desire to portray oneself in a good way. Furthermore, these prejudices vary from one nation to another.

This raises a crucial question – are such measures, even such efforts, intrinsically flawed?

The Global Flourishing Study

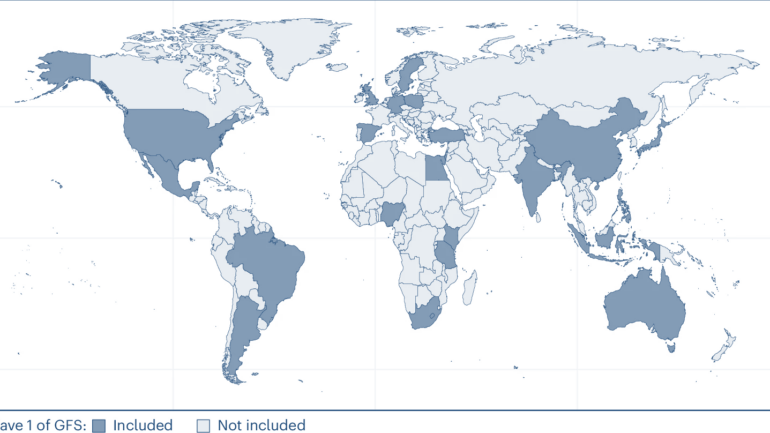

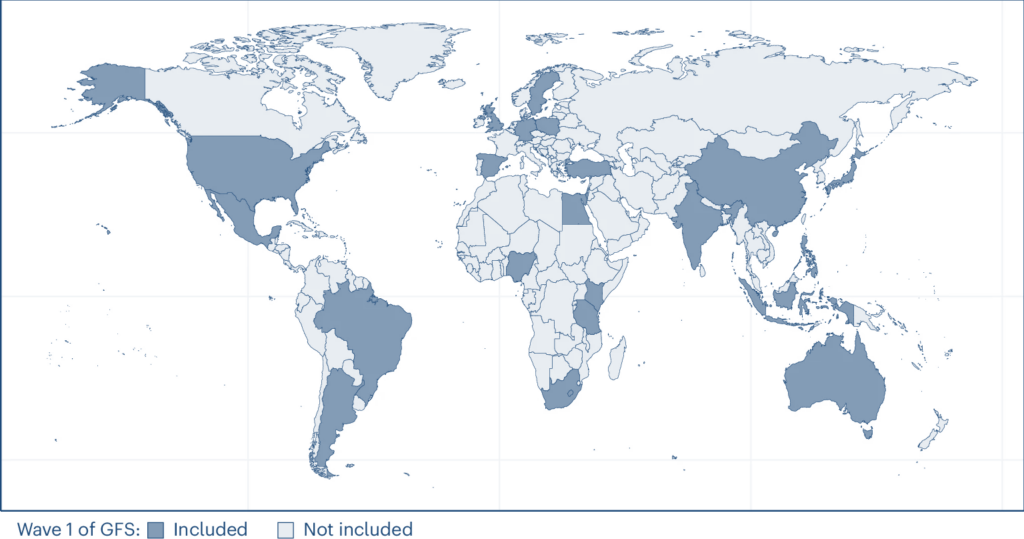

Amid these challenges emerges possibility – the Global Flourishing Study (GFS). A large-scale, open-access, 5-year longitudinal panel study involving over 200,000 participants across 22 geographically and culturally-diverse countries on all six populated continents, using nationally representative sampling within each country, it’s primary goal was to expand understanding of the distribution and determinants of flourishing around the world, particularly in non-Western contexts, and to identify patterns that are universal versus culturally specific.

Image: Countries included in the study; Source: Global Flourishing Survey

‘Flourishing’, according to the GFS, is defined as “the relative attainment of a state in which all aspects of a person’s life are good, including the contexts in which that person lives”. It is viewed as multidimensional, encompassing individual aspects like health, happiness, meaning, character, relationships, and financial security, and also includes communal well-being.

The first wave’s preliminary findings, which were mostly gathered in 2023, look at composite thriving in relation to demographic characteristics and past childhood experiences. Contrary to previous studies that suggested a U-shaped pattern, the findings reveal that, generally speaking, thriving tends to grow with age from ages 18 to 49 onwards; this might mean that young people are not doing as well as they formerly did. Though the amounts differ greatly by nation, better thriving is typically linked to marriage, work, and attendance at religious services.

Positive correlations were also found between adult thriving and childhood experiences such as positive parental connections, subjective financial comfort, lack of maltreatment and feeling connected. Attendance at religious services is one of the most consistently positive variables linked to well-being across nations and results.

Rethinking Policy Priorities

The GFS has limits despite its size. While its questions cover a wide variety of issues, they aren’t customized to different cultural settings, and twenty-two nations hardly scratch the surface of global variation. Additionally, maintaining a representative sample over a period as large as five years raises the time-inconsistency problem.

This is where governments must prioritize gathering solid, culturally appropriate data on what people really care about. This entails conducting frequent, nationally representative surveys, asking pertinent local questions, and, ideally, doing longitudinal research. Finding a few common metrics — simple, well-written questions about meaning or life satisfaction — that may provide helpful global comparisons is just as crucial.

The very purpose of policy has to be carefully reconsidered. Economic growth is important, but so is building meaningful, connected, and purposeful lives.

Read: VanderWeele, T.J., Johnson, B.R., Bialowolski, P.T. et al. The Global Flourishing Study: Study Profile and Initial Results on Flourishing. Nat. Mental Health (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00423-5