AI Dolittle: Cracking Animal Tongues into Compassion Code — Machine Learning Cracks Interspecies Chat

From elephants calling each other by names to whales using family dialects, groundbreaking AI research is unlocking the hidden languages of the animal kingdom. Scientists are now using machine learning to decode distress calls, happiness signals, and even cross-species translation. Could we soon talk to crows, dolphins, and sperm whales? The future of interspecies communication is closer than you think.

Want to know how elephants ‘name’ their friends—and why this changes everything? Dive into the full story!”

Every one of us who have ever had a pet found it easy and exasperating each time our loved animal was delighted to see us, or was suffering in silent. We always wondered what if they could speak. Early this month Baidu. owner of China’s largest search engine, has filed a patent with China National Intellectual Property Administration proposing a system to convert animal vocalizations into human language, according to a patent document filed by the company. Google Playstore even has a Dog Language Translator App that claims to help you to understand the emotions of your beloved dog by just simply recording human or dog voices, and start understanding each other.

Per The Earth Species Project, working on frontier AI to amplify the voices of nature it is only a matter of time when we will be able to decode the language of animals. “With exponential advances in AI and Large Language Models, decoding animal communication is no longer a question of if—it’s when” claims the project’s website. The project is building the first-ever large language models models designed to analyze data from species across the Tree of Life. “By listening more deeply, we can unlock a new relationship with the rest of nature,” it says . The Coller-Dolittle Prize, offering cash prizes up to half-a-million dollars for scientists who “crack the code” is an indication of a bullish confidence that recent technological developments in machine learning and large language models (LLMs) are placing this goal within our grasp.

Meanwhile, a team of researchers have gathered evidence using machine learning that wild African elephants address one another with individually specific calls, somewhat like we call each other by our names, according to a research paper titled ‘African elephants address one another with individually specific name-like calls’ published in Nature. Listening to sperm whales has taught Shane Gero, a whale biologist at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada, the importance of seeing the animals he studies as individuals, each with a unique history.

Humans and other animals generate a range of communication signals – sounds, movements, or chemical signals (pheromones) – that constitute distinct data types. Through advanced machine learning analysis, researchers collaborating with animal welfare experts are trying to decode these patterns to find out the emotional state of animals — from distress to happiness.

Scientists are now investigating an even more ambitious application: leveraging universal linguistic structures (like syntax rules and contextual relationships between “words”) to develop cross-species translation systems. This approach focuses on broader patterns rather than specific vocalizations, theoretically enabling direct communication across biological boundaries. Though still speculative, such breakthroughs could fundamentally transform interspecies understanding and ecological conservation efforts.

Personal names are a universal feature of human language, yet few analogues exist in other species. While dolphins and parrots address conspecifics by imitating the calls of the addressee, human names are not imitations of the sounds typically made by the named individual. Labeling objects or individuals without relying on imitation of the sounds made by the referent radically expands the expressive power of language. Thus, if non-imitative name analogues were found in other species, this could have important implications for our understanding of language evolution.

The authors of the elephant study published in Nature used machine learning to demonstrate that the receiver of a call could be predicted from the call’s acoustic structure, regardless of how similar the call was to the receiver’s vocalizations. Moreover, elephants differentially responded to playbacks of calls originally addressed to them relative to calls addressed to a different individual. Their findings offer evidence for individual addressing of conspecifics in elephants. They further suggest that, unlike other non-human animals, elephants probably do not rely on imitation of the receiver’s calls to address one another.

Gero, has spent 20 years trying to understand how whales communicate. In that time, he has learnt that whales make specific sounds that identify them as members of a family group, and that sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) in different regions of the ocean have dialects, just as people from various parts of the world might speak English differently.

Over the last few years, AI-assisted studies have found that both African savannah elephants (Loxodonta africana)1 and common marmoset monkeys (Callithrix jacchus) bestow names on their companions. Researchers are also using machine-learning tools to map the vocalizations of crows. As the capability of these computer models improves, they might be able to shed light on how animals communicate, and enable scientists to investigate animals’ self-awareness — and perhaps spur people to make greater efforts to protect threatened species.

Beyond creating chatbots that woo people and producing art that wins fine-arts competitions, machine learning may soon make it possible to decipher things like crow calls, says Aza Raskin, one of the founders of the nonprofit Earth Species Project. Its team of artificial-intelligence scientists, biologists and conservation experts is collecting a wide range of data from a variety of species and building machine-learning models to analyze them.

Having decoded a few of these codas manually, Gero and his colleagues began to wonder whether they could use AI to speed up the translation. As a proof of concept, the team fed some of Gero’s recordings to a neural network, an algorithm that learns skills by analyzing data. It was able to correctly identify a small subset of individual whales from the codas 99 percent of the time. Next the team set an ambitious new goal: listen to large swaths of the ocean in the hopes of training a computer to learn to speak whale. Project CETI, for which Gero serves as lead biologist, has deployed an underwater microphone attached to a buoy to record the vocalizations of Dominica’s resident whales around the clock.

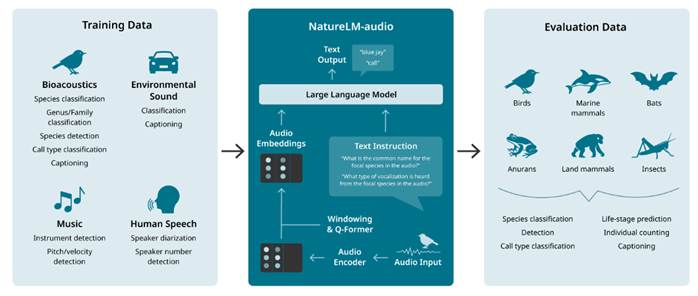

Table 1 Image Source: Earth Species Org

Earth Species Projcts has developed NatureLM-Audio is the world’s first large audio-language model for animal sounds. Trained on a vast and diverse dataset spanning human speech, music, and bioacoustics, it brings powerful AI capabilities to the study of animal communication. It can analyze massive datasets in minutes rather than months, accelerating research at an unprecedented scale and it is only a matter of time when the bark of our dog will be translated as a sentence that we can understand and respond to.