Why Finance Must Finally See the Forests – Southeast Asia Edition

The ‘real economy’ — a tangled realm of manufacturing, building, and agriculture — is struggling with the constraints of nature. Aligning capital flows with the pressing need to preserve and replenish the very natural capital that is essential to future prosperity is both a challenge and an opportunity for the financial sector. Ignoring nature risk will lead to stranded assets and unstable finances; it is no longer a feasible strategy.

For far too long, economists, accustomed to the sophisticated abstractions of models and markets, have viewed nature as a welcoming environment, a resource that can be used for free, or even a nice amenity. ‘Externalities’ were treated like pests – pollution or habitat loss, for example – that somehow existed beyond the market and were the responsibility of governments or possibly altruistic individuals. But literally, the ground is moving beneath our feet. The recently released ‘Financing our Natural Capita’ guide, developed by consulting giant Oliver Wyman and the Singapore Sustainable Finance Association and its partners, marks a significant shift in perspective: nature is now a balance sheet item, and a fairly distressed one at that.

Natural Capital

Consider nature as ‘natural capital’ — a dynamic stock of resources including forests, water, soil, and biodiversity that produce a steady stream of vital ‘ecosystem services’ — rather than as a static picture postcard. These are not small-scale comforts, they are essential to human existence and economic activity. Try managing a contemporary economy without pollination, rich soil, climate regulation and water purification.

The issue? This capital supply has been depleting at an alarming rate. Six of the nine ‘planetary boundaries’ that scientists say are safe operating limitations for human beings on Earth have been crossed. This is an economic catastrophe, not just a complaint from environmentalists. Companies and, consequently, financial portfolios face real ‘nature-related risks’ as a result of the deterioration of these natural resources. New rules may cause revenues to decline, costs to soar, or customers to just stop buying. As a result, investors and lenders need to be aware of these risks.

The report provides a practical road map for financial institutions (FIs) in this situation. It accurately points out that financial institutions typically don’t have significant, direct effects on the environment themselves; instead, the risk they face comes from the businesses they invest in or lend to. The vital initial step? Finding the places in their extensive portfolios where natural risks truly bite, known as a ‘materiality assessment.’

Handling Localized Risks

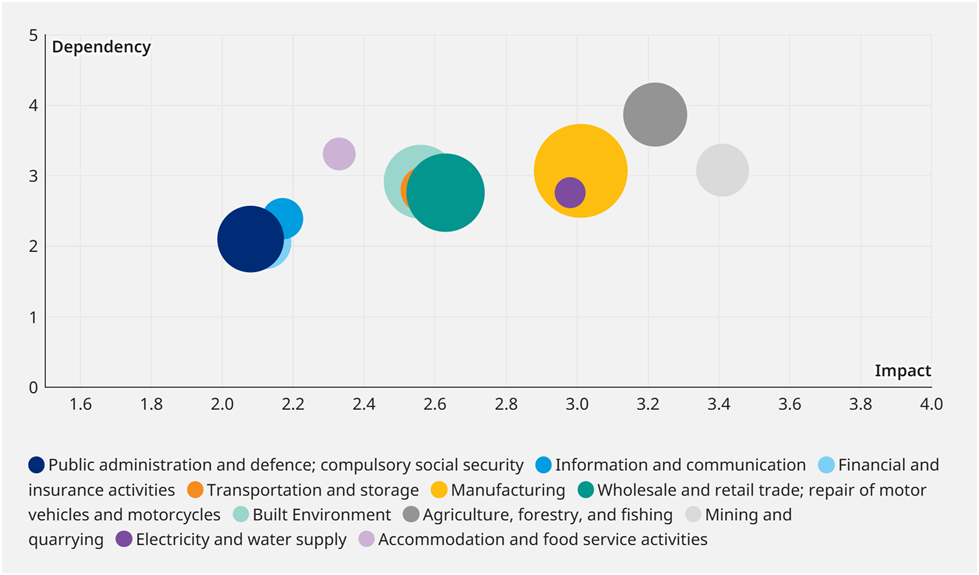

Southeast Asia, for example, paradoxically rich in natural capital yet heavily dependent on basic industries like mining and agriculture that inevitably affect and depend on nature, is highlighted in the guide. A clear picture shows up when you compare the region’s GDP to these dependencies and impacts: major industries like mining, manufacturing, real estate, and agriculture are at serious risk from nature. This is data speaking.

Image: Key economic sectors impacted and/or dependent on nature in Southeast Asia; Source: Oliver Wyman and Singapore Sustainable Finance Association

Nature risk, however, is incredibly localised. In Thailand, where drought is common, a rubber plantation confronts different physical dangers from drought than one in a more water-secure area, while strong national water infrastructure and policy may reduce a water-stressed Singapore’s data centers from physical danger.

The necessity of a multi-layered assessment is extremely important, progressing from a broad sector study to the integration of local ecosystem integrity and, most importantly, a close examination of value chains. Analyzing a sector without taking value chain or geography into account is like attempting to traverse a maze while wearing a blindfold, as experts sagely point out. Despite their granularity limits, tools such as ENCORE and the WWF Risk Filter become essential compasses.

‘Transition risks’ are a significant concern beyond the physical shocks. These include new regulations, changes in technology and shifting consumer tastes as a result of society’s reaction to environmental degradation. For example, Southeast Asian palm oil producers face a significant transition risk from the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR). All of a sudden, environmental performance determines whether the market rewards or penalizes.

Then there are the ‘reputational risks,’ where a brand’s financial worth and reputation might be destroyed by an association with environmental harm. One well-known example is boycotts due to deforestation associated with the manufacturing of palm oil.

Nature Funding – The Way Forward?

It’s not all bad news, however. ‘Nature funding’ is the opposite of risk and represents opportunity. The guide promotes a broad definition that includes actions that deliberately mitigate adverse effects or generate beneficial ones. This involves funding the shift to a circular economy, sustainable water management, pollution avoidance, ecosystem restoration (think regenerative agriculture) and sustainable supply chains, going far beyond specialty conservation bonds.

These opportunities aren’t completely new either; they’re just being formally acknowledged and expanded, as evidenced by Singapore’s United Overseas Bank’s internal analysis, which shows that roughly 60% of its current green/sustainability-linked loans already fund nature activities. The Circular Economy ETF from BNP Paribas Asset Management and the sustainability bond for Manila Water from UBS are two specific instances of how money is moving in the direction of these solutions.

There are however several obstacles in the way of turning this promise into common financial practice, particularly given how incredibly complicated and hyper-local nature is, in contrast to climate change, which has centered around carbon as a major (although flawed) indicator and global scenarios. The effort of creating consistent data and analytics is enormous.

Global climate models are more simpler than localized stress testing scenarios, which are crucial for physical risk assessment. It will take a great deal of cooperation to define distinct ‘sectoral routes’ for nature-positive changes. This calls for concerted action from the financial sector allocating capital, the real economy implementing sustainable practices, regulators offering guidance and governments establishing explicit mandates.

Read ‘Why Financial Institutions Should Bank On Natural Capital’ by Oliver Wyman and the Singapore Sustainable Finance Association here.